few hundred people have gathered around the Pagani Huayras, Bugatti Veyrons, and McLaren P1 GTRs arrayed in a shopping plaza in Walnut, a city near the eastern edge of Los Angeles County in the San Gabriel Valley. “The spec is sick,” says one person. “Look at that wing,” says another as onlookers post pictures to their social accounts. The collective value of the hyper-cars and other exotic cars on display is said to be about $40 million to $50 million. “There’s probably nowhere else you could see a lineup of multi-multimillion dollars’ worth of cars like this,” says Elie Rothstein, the owner of a car stereo company, who’s brought his newly acquired Ferrari 488 coupe. “Even I was impressed today to see the first U.S. Lamborghini Centenario here. You may never see that car again in your life.” It sells for around $2 million.

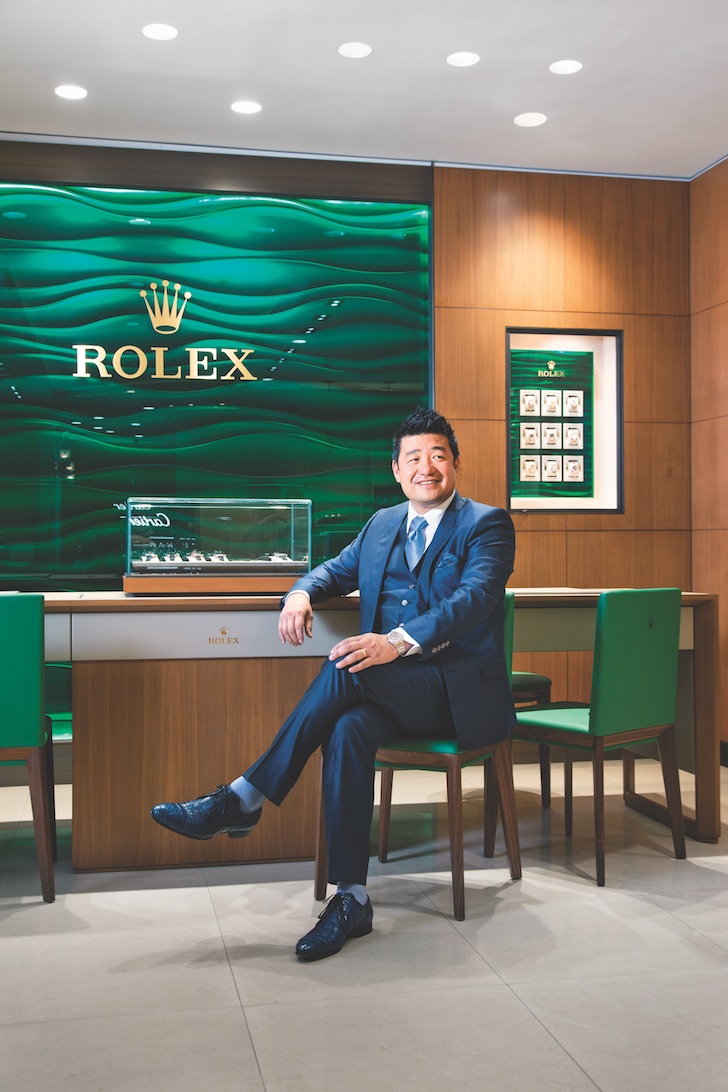

The man putting on this monthly meetup is 51-year-old David Lee, who happens to own the shopping plaza as well as its premier store, Hing Wa Lee Jewelers. That’s where you’ll find several of the car owners eating breakfast at a VIP table surrounded by a few million dollars’ worth of watches in display cases. Rolex is the top seller here, followed by the small Swiss brand Richard Mille (average price: $180,000), which is on the wrists of a couple of the drivers here today. In the last few years, this branch of Hing Wa Lee and its sister store in San Gabriel have vaulted to become two of the highest-grossing sellers of fine timepieces in the United States. “Hing Wa Lee is one of our top ten independent retailers in the country,” says Edouard d’Arbaumont, North America president of luxury Swiss watchmaker IWC.

Lee was born in Hong Kong and moved with his family to Whittier when he was nine. After graduating from USC, he transformed his father’s wholesale gemstone-carving and jewelry business into the force it is today. Along the way, Lee has had his hands in a number of seemingly disparate ventures, from real estate management and development to investing (in a bottled iced tea company and tech start-ups).

More than a hobby, exotic cars are part of his portfolio, too. A Porsche, Pagani, and McLaren of his are on display at the meet-up, and Lee has one of the world’s most impressive Ferrari collections—22 in all, including an example of every Ferrari supercar built since 1985. His vehicles are often featured on the Web series of fellow collector Jay Leno; some of those he purchased for $1 million are worth two to three times as much now. “You can’t get that kind of increase in the last few years with real estate. It’s making money for me every day basically,” says Lee, who is wearing Dolce & Gabanna jeans and a Pagani racing-style polo shirt. He cohosts a collectible car meet-up at Arcadia’s Santa Anita racetrack with mega-dealer Rusnak Motors every three months as well and has an auto-dealer license for those times when he wants to broker sales.

Where other collectors often just garage their cars, Lee actually drives his rare makes, but his ties to the upper echelons of the car world also benefit his watch business: Many of the people Lee has met on the circuit have become Hing Wa Lee clients. “There are those guys that feel, ‘If I buy a Pagani or a LaFerrari, I should wear a Richard Mille watch,” says Lee. “The price point is starting at 130, not 15. There’s a whole thing of people buying that to feel like, ‘I’m at a different level.’”

Albert Napoli, who teaches entrepreneurship at USC’s Marshall School of Business, has hosted Lee each semester for the past two years to speak to his students (Lee serves on Marshall’s Board of Leaders as well).“They all cater to the same customer,” Napoli says of Lee’s various pursuits. “So that person who buys a $30,000 Rolex might also be the same person who invests in a real estate development with him or buys a $2 million Ferrari.” Lee says that many of his clients have manufacturing businesses in China. “Their wives and children live here, and they go back and forth from China,” he adds.

The average sale at the two stores is $10,000, according to Lee, who notes that despite a global downturn in the watch market, his sales are up 8 percent over last year. One reason business has remained strong is his clientele: “For Asian customers, there is a whole idea of collecting watches, a culture that Americans don’t really have except for a small amount of people who will do that.”

Friendly and earnest, Lee holds his success out as an equalizer, trumpeting it as something anyone can achieve. On his Instagram—which has 730,000 followers—and his company website, he sells himself as a model businessman with a philosophy everybody can follow. “I call it the Three Pillars: Work hard, work with perseverance, and work with integrity. It’s very much a Chinese-culture thing,” says Lee, whose father, Hing Wa, would push his three kids with aphorisms like “Work harder than you think what ‘working hard’ means.”

Lee’s great-grandfather was the first in the family to come to the U.S., working for a railroad company in San Francisco. (He died there alone.) But the family wasn’t able to escape China’s pervasive poverty. “There were all kinds of stories about them eating these water roots and stuff like that because they didn’t have any food,” Lee says. So Hing Wa and his brother set their sights on Hong Kong, which was under British control. One way to get there was by being smuggled onto boats bound for Macau, then jumping out and swimming to Hong Kong using a flotation device. “My dad said half the people wouldn’t make it because they would get hypothermia,” he recalls.

After Hing Wa and his brother made the perilous trip, he eventually became a master of carving jade and malachite. Those skills led to an invitation from the founder of the International Gem & Jewelry Show to help with the restoration of Asian antiquities at the Smithsonian in the mid-’70s. So he and his wife, Annie, moved with David and his sister to Bethesda, Maryland, and eventually had another son before relocating to Whittier. To make ends meet they rented a tiny wholesale showroom on Hill Street in downtown L.A.’s Jewelry District to run Hing Wa Lee. David joined his dad there decades later, in 1992, after getting his business degree.

By then, the region’s Chinese population had left Chinatown behind for Monterey Park, which became the first majority-Asian city in America in 1990. Less than one tenth of a percent of places in the United States that are recognized by the federal census are majority Asian, and most of them are in California. Walnut, where Lee holds the monthly meet-ups, is among ten majority-Asian cities in the San Gabriel Valley. The others are Arcadia, Monterey Park, Rowland Heights, Diamond Bar, Temple City, Alhambra, San Gabriel, Rosemead, and San Marino. The last is where Lee lives with his wife and teenage son (their daughter is studying at USC); it’s also one of the priciest zip codes in L.A. County.

Rather than being way stations for people waiting to be assimilated in the great melting pot, many of these areas are, to use a word Wei Li wrote a book about when she was an American Studies professor at Arizona State University, ethnoburbs—multiracial communities that have a mix of socioeconomic levels and that allow immigrants to maintain their cultural identity. That’s essentially why the San Gabriel Valley is a well-known locale in China. “For the upper-middle class, they aim at immigration because of their children’s education,” says Li. “For the super-rich, some are hiding their wealth for whatever reasons. Many of these newly rich people do not necessarily have good English skills, nor do some of them intend to master English. So their choice of location for a residence is limited to places like the valley.”

The large amounts of transnational capital and the steady influx of the wealthy and not-so-wealthy from mainland China have fueled real estate prices and luxury home building over the past decade in the San Gabriel Valley. This winter an Art Deco-style Sheraton hotel is opening in San Gabriel, funded by people here on EB-5 visas, which allow would-be immigrants to gain green card status by making investments of at least $500,000 that would create a minimum of ten jobs. (The new Waldorf Astoria in Beverly Hills received $150 million in EB-5 financing, while the project that will add two towers behind the Century Plaza in Century City is receiving $450 million.) Next year the SGV will see the opening of another hotel, a Hyatt Place. It and the Sheraton will join the 13-year-old Hilton that sits beside Valley Boulevard, a street lined with Chinese-owned businesses, and across from San Gabriel Square, a sprawling shopping plaza that is home to Hing Wa Lee’s main competitor, Chong Hing Jewelers (which sells such watch brands as Patek Philippe and Bulgari).

The gravitational center of the area is shifting, too, with new restaurants opening at a quicker pace in the cities of Rowland Heights, Diamond Bar, and Walnut—sometimes referred to as the Eastern District—than in older Chinese American communities such as Monterey Park. And the new restaurants tend to be more refined than their “very humble-looking” predecessors, says Charlie Gu, a director with China Luxury Advisors, which put together a Chinese tourist outreach program for the Beverly Center.

In Arcadia the Westfield Santa Anita shopping mall has catered to its large Asian clientele in part by appealing to their bellies. Along with adding stylish hot pot (Hai Di Lao) and dumpling (Din Tai Fung) powerhouses from China and Taiwan, it has installed millennially appealing Asian restaurants in a brick-lined passageway it calls a “food alley.” This is coveted territory. Westfield helped shoot down an effort by Rick Caruso a few years ago to build a version of The Grove on the adjoining property. And a developer is hoping to open the Province in San Gabriel next year, with, as its website coos, “global luxury stores, fashionable restaurants and elite services typically only found on the West Side of Los Angeles like The Grove or the Brentwood Country Mart.”

Seeing the changing terrain back in the early 1990s, Lee urged his father to take the wholesale business retail. They closed the downtown shop and opened a store in San Gabriel, where Lee injected his passion for timepieces into the mix. His break came in 1995, when he landed a coveted spot as an authorized Rolex dealer. It took some doing. He flew to Switzerland two years in a row to court the company at the big Baselworld watch fair. Unable to get an appointment with a sales executive, he kept dropping by the booth for a few days until he was finally granted a one-minute meeting. “Rolex told him no so many times,” says Napoli. “There’s this large Asian population in the San Gabriel Valley that no one knew how affluent they really were, but David did.”

In 2004, the Walnut store made its debut in the shopping plaza that Lee and his father had built. (Lee’s brother serves as the company’s vice president. Their sister, a doctor, is not part of the business.) A decade later, the family patriarch died, and in 2013, Lee swapped the San Gabriel store for a much larger showroom with domes, arches, and columns that are supposed to recall the architecture of Geneva. The pianist Lang Lang (whom Lee recently called “my bro” on Instagram) performed at the opening.

Unlike most watch stores, Hing Wa Lee provides each brand with its own mini boutique area and its own style of furniture as if it were a department store. Lee also doesn’t move his timepieces to a vault at night. “It’s time-consuming, and there’s a lot of wear and tear. I was able to design the building so the store itself is a walk-in vault. We’re the only ones that have insurance that allows us to leave everything out overnight,” he says. Security is of paramount concern for him. In 2016, five masked men, one with an assault rifle, attempted to rob his Walnut store but fled empty-handed after security guards shot at them.

There was a time when Asian tourists to the SGV—an estimated 350,000 people a year—accounted for 40 to 50 percent of Lee’s annual sales. SGV tour guide Vincent Zhang of GOtrip would often steer tour buses to Hing Wa Lee and get a commission on sales. The tourists would want to stay in the valley because of the number of restaurants and omnipresence of Mandarin speakers. But that is changing. Visitors from China, who account for more visitors to L.A. than from any other country, are less heavily focused on luxury shopping. Now, says Zhang, “they want some special local stuff ,” such as eating baby-back ribs (“they like American barbecue”), visiting downtown L.A., and taking motorcycle and boat excursions.

Residents have more than made up for the drop at Hing Wa Lee. And there are, of course, Lee’s various other gigs, including Brilliant Realty, a commercial and residential agency run by his wife, Katherine. Its property management arm oversees the Walnut shopping plaza as well as apartment buildings. Declining to note what other property he owns, Lee will say only that he has “significant” real estate investments overseas. But he did help launch a high-end sushi restaurant, Oo Toro, next door to his Walnut boutique. (As for the Chinese-language magazine Phoenix listed on his Website, it’s no longer in business.)

“I’m a serial entrepreneur,” he says. “I like to start businesses, and I like to run them.” For one of his newest ventures, he’s starting a company that remakes vintage Ferraris with up-to-date engines. For another, Lee is looking to break into the China market with Dennis Wong, cofounder of YOR Health, to sell the company’s health products in China.

The two are members of a group Lee founded called the CEO Club, an organization of 15 to 20 Chinese men who are all heads of their own companies—real estate and financial services professionals, restaurateurs, developers, and fashion label owners. “It’s like a little fraternity for us,” says Lee. The annual membership fee is $10,000. “I’m not the ‘Asian’ kind of guy. My wife is African American. I don’t like to identify with one type of group,” Wong says. “But because of David, I knew he would bring friends who were going to be kind of like him. They are just solid people. It’s just nice having somebody at your level to bounce things off of once in a while.”